We are living through a global biodiversity challenge that demands urgent and innovative financing solutions. According to the UNDP, biodiversity is declining faster than at any time in human history, with over ten million hectares of forest lost annually, two-thirds of the oceans impacted by human activity, and approximately 200 species going extinct every day.[1] Despite this alarming loss of nature, global conservation efforts remain drastically underfunded. Currently, governments and private actors together invest around $124 billion per year in biodiversity protection.[2] However, according to a joint report by The Nature Conservancy, the Paulson Institute, and the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability, the world needs between $722 and $948 billion annually through 2030 to effectively safeguard ecosystems.[3] This represents a yearly funding gap between $598 and $824 billion, a major obstacle to reversing biodiversity loss.

In this context, a new financial instrument is gaining attention: biodiversity credits. These credits aim to channel private capital into conservation by transforming measurable positive outcomes for nature into verified, tradable units. This blog aims to explain how biodiversity credits can be leveraged to address the funding gap. They offer a market-based approach to support biodiversity alongside existing public and philanthropic efforts. In this article, we explore what biodiversity credits are, how they work, and present selected case studies that illustrate their emerging applications across different regions and ecosystems.

What Are Biodiversity Credits, and How Do They Work?

Biodiversity credits are market-based instruments that represent a quantified positive impact on nature, such as the conservation of a forest, the restoration of a wetland, or the protection of a threatened species. They are often compared to carbon credits because both create tradeable units based on measurable environmental outcomes, which can be bought and sold in voluntary or regulated markets. However, the objectives and metrics of each differ substantially. Unlike carbon credits, which are standardized around a single metric (tons of CO2), biodiversity credits are more complex: nature is not interchangeable, and its value cannot be reduced to a single unit.[4]

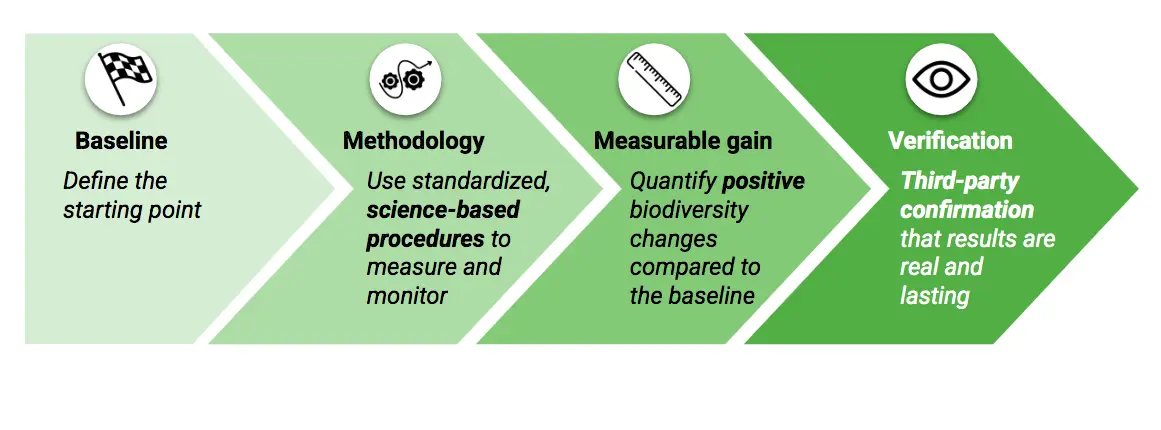

In simple terms, a biodiversity credit is a verified unit of positive biodiversity outcome that results from conservation actions and is measured against a defined baseline. This baseline reflects what would happen in the absence of the project. The definition, as outlined by the Biodiversity Credit Alliance (BCA) is based on four key elements: a clear baseline, credible methodology, measurable gain, and verified outcome. These elements are designed to ensure that credits represent real and lasting benefits for nature.[5]

Figure 1. Key Elements for Issuing a Biodiversity Credit [6]

Once these conditions are met, the process involves designing the project, applying a standardized measurement methodology, and undergoing third-party validation and verification. Verified credits can then be issued and sold through voluntary markets or direct agreements.

Biodiversity credit schemes can take diverse forms. According to a global review by Pollination, credit-generating activities include habitat restoration, invasive species removal, species recovery actions, and the establishment of conservation easements.[9] The review highlights that methodologies vary by region and ecosystem type, and many schemes are still in the pilot or demonstration phase. It also stresses the importance of aligning biodiversity credit schemes with global goals such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.[10]

While both carbon and biodiversity credits seek to address critical environmental challenges through market mechanisms, carbon credits focus on climate mitigation, biodiversity credits are outcome-based instruments that focus on conserving life-supporting ecosystems. They are not interchangeable but can complement each other, particularly in projects that deliver both climate and biodiversity benefits.

Beyond these general principles, some initiatives have also proposed ways to express biodiversity outcomes in terms of ecological “return per hectare.” For instance, the Wallacea Trust defines one biodiversity unit as a 1% median gain in biodiversity indicators per hectare, helping to translate complex ecological benefits into a standardized metric.[11]

Real World Examples

Several countries are already experimenting with biodiversity credit schemes. Here are four cases that illustrate different approaches:

- Colombia – El Globo Habitat Bank: In the Andes region, the El Globo project by Terrasos transformed degraded pastures into restored native cloud forest and pioneered the issuance of voluntary biodiversity credits. By November 2022, the initiative had expanded into a network of 12 habitat banks managing over 7,000 hectares, with compensation mechanisms designed for an additional 31,000 hectares. The ambition is to protect more than 100,000 hectares by 2030, directing significant private capital toward conservation.[12] According to Climate Collective, Terrasos has generated over USD $1.8 million from the sale of these biodiversity credits in Colombia, reinforcing its contribution to high-integrity biodiversity markets.[13] The project protects habitat for 290 bird species, 76 mammals, 24 reptiles, 8 amphibians, 12 fish species, and 29 butterfly species, all monitored through a protocol aligned with the Biodiversity Credit Alliance framework.[14]

- Brazil – CRA Titles and Jaguar Conservation: Brazil’s Forest Code allows rural landowners with excess native vegetation to issue Environmental Reserve Quotas (CRA). These credits can be sold to others who need to meet legal conservation requirements.[15] In parallel, initiatives in the Cerrado region are using jaguar habitat restoration to generate voluntary biodiversity credits linked to species protection.[16]

- Niue – Ocean Conservation Credits: This small Pacific island nation created the Ocean Conservation Commitments (OCC), allowing supporters to sponsor 1 km2 of marine area for 20 years. The funds finance enforcement, monitoring, and local stewardship of Niue’s marine protected areas, covering its entire Exclusive Economic Zone.[17] Launched in September 2023, the OCC program has raised approximately USD $4.27 million toward a goal of USD $10.98 million. Annual reports are planned to track enforcement activities, community engagement, and ecological status of the 127,000 km² Niue Nukutuluea Multiple-Use Marine Park.[18]

- Australia – Nature Repair Market: In 2023, Australia passed legislation to create the first regulated voluntary biodiversity market. Under the Nature Repair Market, landholders can generate credits for projects that improve or protect ecosystems, following approved measurement standards. These credits can be purchased by businesses or governments seeking to support nature-positive outcomes. The government’s Clean Energy Regulator has noted that biodiversity certificates typically command a higher premium than carbon credits, reflecting their focus on biodiversity outcomes; for comparison, Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCU) trade around USD $21.21 per metric ton of CO₂ equivalent, while biodiversity credits are expected to fetch even higher prices, depending on habitat type and project scope.[19]

Challenges and Opportunities Associated

According to the civil society statement on biodiversity offsets and credits (2024) there are multiple considerations that should be taken into account to ensure biodiversity credits are effective and fair:[20]

- Avoiding greenwashing and commodification: Biodiversity credits must be backed by robust standards and safeguards so they are not used to mask harmful practices or reduce the intrinsic value of nature.

- Ensuring equity and participation: Indigenous Peoples and local communities (IPLCs) should be central to decision-making and benefit-sharing. Mechanisms like Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) are essential.

- Prioritizing ecosystem integrity: Projects must ensure that biodiversity outcomes are real, measurable, and not used to justify ecosystem destruction elsewhere.

- Complementing, not replacing, conservation: Credits should add to, not replace, direct funding for protected areas and on-the-ground conservation.

- Strengthening regulation and accountability: Governments must provide clear rules, transparent governance, and credible monitoring to guarantee the permanence and integrity of credited outcomes.

- Transparency and public access to information: All data and methodologies should be publicly available to build trust and accountability.

- Preventing perverse incentives: Credit schemes should avoid creating incentives that could harm biodiversity, such as allowing damage in one area to be offset elsewhere.

By integrating these safeguards, biodiversity credits can serve as a strong complement to broader biodiversity strategies rather than as a substitute.

Conclusion

Biodiversity credits alone will not be enough to halt biodiversity loss. However, when designed responsibly, they can help unlock much‑needed funding for conservation. Their long-term success will hinge on credibility, fairness, and ecological ambition.

In the coming years, biodiversity credits have the potential to transform how the world values nature by recognizing and rewarding the services that ecosystems provide. They can help bridge the persistent financing gap, encourage private sector engagement in conservation, and support the livelihoods of communities who act as stewards of biodiversity-rich areas. At the same time, these markets must be developed with a strong sense of responsibility: they must not become a license to harm nature or replace direct conservation efforts.

If developed with strong standards and governance, biodiversity credits could play a meaningful role in reducing the biodiversity financing gap and supporting a more nature‑positive economy. Innovations such as the Wallacea Trust’s hectare-based methodology illustrate how science can guide these markets toward measuring biodiversity outcomes more transparently. Ensuring genuine and lasting benefits for ecosystems and the communities that depend on them will require collaboration between governments, civil society, investors, and local actors. By aligning ecological ambition with financial innovation, biodiversity credits can become a catalyst for scaling up conservation in ways that are both equitable and effective.

—

Fernanda Benítez, recently graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in Actuarial Science from the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM). At HPL, she has contributed to the execution of +5 consulting projects by conducting research, performing comparative studies, structuring thematic Bond Frameworks and preparing reports for development banks and sovereigns in LAC. Previously, Fernanda worked at Citigroup as a ICG Operations Summer Analyst, where she conducted comparative analysis of KPIs and collaborated in implementing improvements in tracking processes. Prior to this, she was an intern at Samsung Electronics Mexico, where she generated detailed reports on training-related KPIs and contributed to the creation of innovative materials. Her focus is on finance, sustainable finance, consulting, and corporate banking.

—

References

[1] United Nations Development Programme. (2025). Biodiversity crisis must be urgently addressed. China Daily via UNDP. Available online.

[2] Deutz, A., Heal, G. M., Niu, R., Swanson, E., Townshend, T., Zhu, L., Delmar, A., Meghji, A., Sethi, S. A., & Tobin‑de la Puente, J. (2020). Financing Nature: Closing the global biodiversity financing gap. Paulson Institute; The Nature Conservancy; Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability. Available online.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria, S.A. (n. d.). What biodiversity credits are and how they help protect nature. Available online.

[5] Biodiversity Credit Alliance. (2024). Definition of a biodiversity credit (Issue Paper No. 3; Rev 220524). Available online.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Pollination. (2023). State of voluntary biodiversity credit markets: A global review of biodiversity credit schemes. Available online.

[9] Pollination. (2023). State of voluntary biodiversity credit markets: A global review of biodiversity credit schemes. Available online.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Replanet.Measuring biodiversity gain. Available online.

[12] IDB Lab. (2025). How do blue bonds and biodiversity credits foster mobilization for resilience and conservation? Available online.

[13] Climate Collective. (2024). Innovating Habitat Banking and Biodiversity Credits: Terrasos joins Climate Collective Members. Available online.

[14] Terrasos (2024). Protocolo para la Emisión de Unidades de Biodiversidad Voluntarias: En el camino a economías en armonía con la naturaleza (Versión 4.0). Available online.

[15] ((o))eco – Jornalismo Ambiental. (2015). What are environmental reserve quotas (CRAs) [Dicionário Ambiental]. Available online.

[16] Regen Network. (2024). Regen Network reports traction for biodiversity credits sales. Medium. Available online.

[17] Thomson Reuters. (2023). Pacific islands nation Niue sells stakes in ocean to fund conservation. Reuters. Available online.

[18] Carreon, B. (2025). Want to sponsor a piece of ocean paradise? How one Pacific island’s novel response to rising seas is paying off. The Guardian. Available online.

[19] Chauhan, H. (2025). Australia launches world’s first legislated voluntary biodiversity credits market. S&P Global Commodity Insights. Available online.

[20] Third World Network. (2024, October 2). Civil society statement on biodiversity offsets and credits. Available online.